Thursday, 30 July 2009

Literature Review for the Review of Elective Home Education

and download either version.

We have yet to read and take it in but at first glance I do not recognise much from my own research and reading.

Very interested to know what others make of it.

Tuesday, 28 July 2009

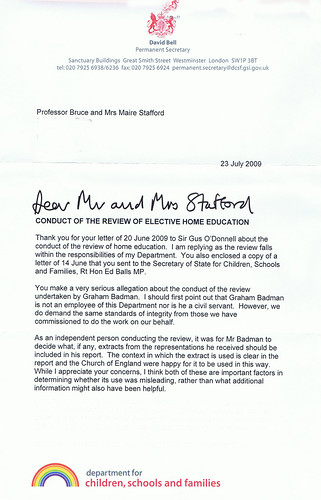

Reply from David Bell, Permanent Secretary, DCSF

David Bell

Permanent Secretary

Sanctuary Buildings Great Smith Street Westminster London SW1 P 3BT

tel: 020 7925 6938/6236 fax: 020 7925 6924 permanent.secretary@dcsf.gsi.gov.uk

Professor Bruce and Mrs Maire Stafford

23-July 2009

CONDUCT OF THE REVIEW OF ELECTIVE HOME EDUCATION

Thank you for your letter of 20 June 2009 to Sir Gus O'Donnell about the conduct of the review of home education. I am replying as the review falls within the responsibilities of my Department. You also enclosed a copy of a letter of 14 June that you sent to the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, Rt Hon Ed Balls MP.

You make a very serious allegation about the conduct of the review undertaken by Graham Badman. I should first point out that Graham Badman is not an employee of this Department nor is he a civil servant. However, we do demand the same standards of integrity from those we have commissioned to do the work on our behalf.

As an independent person conducting the review, it was for Mr Badman to decide what, if any, extracts from the representations he received should be included in his report. The context in which the extract is used is clear in the report and the Church of England were happy for it to be used in this way. While I appreciate your concerns, I think both of these are important factors in determining whether its use was misleading, rather than what additional information might also have been helpful.

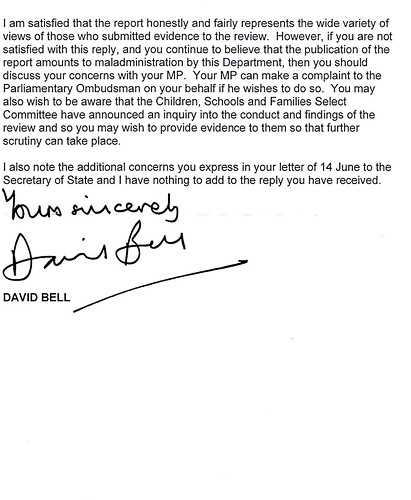

I am satisfied that the report honestly and fairly represents the wide variety of views of those who submitted evidence to the review. However, if you are not satisfied with this reply, and you continue to believe that the publication of the report amounts to maladministration by this Department, then you should discuss your concerns with your MP. Your MP can make a complaint to the Parliamentary Ombudsman on your behalf if he wishes to do so. You may also wish to be aware that the Children, Schools and Families Select Committee have announced an inquiry into the conduct and findings of the review and so you may wish to provide evidence to them so that further scrutiny can take place.

I also note the additional concerns you express in your letter of 14 June to the Secretary of State and I have nothing to add to the reply you have received.

DAVID BELL

department for

children, schools and families

Sunday, 26 July 2009

Letter to UK Statistics Authority

26th July 2009

Richard Alldritt

Head of Assessment

UK Statistics Authority

Statistics House

Tredegar Park

Newport

South Wales

NP10 8XG

Dear Mr Alldritt,

Conduct of the Review of Elective Home Education

On the 11th June 2009 the Department for Children, Schools and Families published its Review of Elective Home Education in England, which was conducted by Graham Badman. In at least two instances associated media coverage alleged that twice as many home education children were known to social care compared to the rest of the population, a claim that was attributed to the report’s author, although it is not made in the published report:

‘The reforms are necessary because twice as many home educated children are known to social services as the normal school-aged population under current arrangements, the report revealed.’

(Woolcock, N. (2009) ‘Home education parents to face council inspections’, Times Online, 11th June, Retrieved from http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/education/article6480288.ece on 26th July 2009.)

‘Children educated at home are twice as likely to be on social services registers for being at risk of abuse as the rest of the population, the head of a government inquiry into home education said yesterday. … Graham Badman, the former director of Kent County Council's children's services, headed the review. He said the ratio of home-educated children who were known to social services was "approximately double" that of the population at large.’

(Anon. (2009) Children educated at home more at risk of abuse’, The Independent on Sunday, 12th June, Retrieved from http://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/children-educated-at-home-more-at-risk-of-abuse-1703220.html on 26th July 2009.)

That the ‘twice as many’ is an official statistic is confirmed by a Department for Children, Schools and Families Freedom of Information response that provides an insight into how the estimate was calculated. The Freedom of Information request was made by Mr. S. Mckie and the response made by Ms S. Thomson on the 24th July (a copy is at http://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/local_authority_evidence). The response is headed Annex, although it is currently unclear to which document it was originally appended. Our concern is that both the press statement and the ‘Annex’ breach the Code of Practice for Official Statistics, in particular Principles 4 (sound methods and assured quality) and 8 (frankness and accessibility), and the Civil Service Code for the following reasons:

1. Quoting to the media the ratio of the two proportions, without stating the actual estimated figures, arguably conveys the impression that the difference is more severe than the actual percentage estimates suggest: 6.75 per cent for home educated children and 3 per cent for the population. A more honest and impartial statement would have involved giving the actual figures and/or mentioning that the difference is only nearly 4 percentage points.

2. The interpretation and presentation of the variables used is misleading. As the above quote from The Independent shows at least one organisation completely misunderstand the nature of the data – ‘known to social care’ is a different administrative category from being registered ‘at risk’. The Department for Children, Schools and Families does not appear to have insisted that The Independent issue a correction to the misleading impression that their attribution to Badman will have created amongst the public.

The Freedom of Information response refers to children known to social care including Section 17 and 47 enquiries under the Children Act 1989. Given the focus of the Review on child safeguarding the inclusion of Section 17 cases in the calculation of the estimate is inappropriate. Section 17 covers the provision of services to children in need and is not an indicator of the risk of child abuse, it includes, for instance, parents requesting a service such as respite care for a disabled child.

Section 47 cases include child protection inquiries but also referrals to social care irrespective of whether or not child abuse is subsequently established. It is likely that home educators are, wrongly, over-represented amongst Section 47 referrals because (concerned) third parties, unaware of the legal right to educate at home, mistakenly contact social services. In some cases the parents will be ‘known to social care’ but there is no suggestion of their children being at risk of abuse. The Section 47 figures, therefore, over-estimate the number of at risk cases amongst the home educating community.

These difficulties with interpreting ‘known to social care’ statistics that arise from Sections 17 and 47 are not mentioned in the Annex, and it is unknown if Badman tried to convey them to the press.

3. A related point that the data may not be comparable. The 3 per cent population estimate relates to individuals aged 5 to 16 years.[1] It is unclear whether the sampled ‘known to social care’ data counted individual children or enquires. It is known that the Section 47 data refers to enquires not children. Each enquiry in any one year for a particular child is separately recorded.[2] Moreover, it is unknown whether the ‘known to social care’ was similarly restricted to children aged 5 to 16 years, or whether, for instance, it included younger children.

4. There are a number of issues arising from the calculation of the ‘known to social care’ estimate that should have been highlighted, at least, in the Annex.

a. The denominator for the estimate assumes a median of 139 registered home educated children per local authority; giving 20,850 (139*150) nationally. The Freedom of Information response rounds this up to 21,000 whilst Badman rounds it down to 20,000 in the report of the Review. The median value of 139 comes from the survey of 90 local authorities. How representative these 90 councils are of all local authorities is unknown. No attempt appears to have been made to correct for response bias.

b. The estimated number of registered home educated children known to social care appears to be obtained by applying a percentage (6.75 per cent) to the estimated total number of registered home educated children (see a above). There are three issues here.

First, according to the Freedom of Information response the percentage applied (6.75 per cent) is the median value taken from a small sub-sample of 25 local authorities (17 per cent of all English local authorities). Again, the representativeness these 25 local authorities is unknown; although our estimate of the mean number of ‘know to social care’ for these authorities (19 compared to 9 for the country has a whole) suggests that they are atypical and have an above average number of cases. For such an unrepresentative sample, even the use of the median percentage is likely to be an over-estimate of the proportion that should be used in national estimates. Thus grossing-up using 6.75 per cent is likely to produce an invalid over-estimate of the number of home educated children ‘known to social care’. Yet no qualifications to the estimate are mentioned in the Annex, and whether Badman tried to convey them to the press is unknown.

Secondly, the Freedom of Information response states that the estimated number of home educated children know to social care is 1,350. However, if the 6.75 per cent was used to derive this estimate then the base used was 20,000 (a figure given in the Review) and not the Annexes’ own population estimate of 20,850 (which would give a higher estimate of 1,407). It’s not clear why a base of 20,000 has been used rather than 20,850 (or a rounded up 21,000).

Thirdly, and as the Freedom of Information response acknowledges, the estimated size of the population is an under-estimate. Many home educators are unknown to local councils. The Review says that the estimated number is 20,000 but ‘it is likely to be double that figure, if not more, possibly up to 80,000 children’. If more home educated children were ‘registered’ with local authorities – and clearly such families exist – then the median proportion of 6.75 per cent for known to social care would be lower; as the base for such calculations would be a larger number. In these circumstances the difference between the percentages for home educated and the population known to social care would narrow. The estimated proportion of known to social care for each of the 25 local authorities should have included a range of estimates using higher estimates of the number of home educated children in each area.

Both the Review report and the Annex ought to have included a range of estimates using different nominators and denominators

You should be aware that we have many other concerns about the conduct of the Review, that the Children, Schools and Families Select Committee has instigated a brief enquiry into the conduct and recommendations of the Review, and that this letter and your response are likely to be blogged at http://maire-staffordshire.blogspot.com/.

We are writing because we believe that the Review does not reach the standard required for such a radical change in the law relating to home education, and that its shortcomings are inevitably reflected in its recommendations. We look forward to hearing from you.

Yours sincerely

Prof. Bruce Stafford

Mrs Maire Stafford.

(sent by email)

[1] The source for the estimate appears to be: DCSF (2006) Children in Need in England: Results of a survey of activity and expenditure as reported by Local Authority Social Services’ Children and Families Teams for a survey week in February 2005: Local Authority tables and further national analysis (Internet only),Statistical Volume, National Statistics, Retrieved from http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/rsgateway/DB/VOL/v000647/vweb02-2006.pdf on 26th July2009.

[2] Department for Children, Schools and Families (2009) Guidance Notes for the Completion of Statistical Return CPR3 Referrals & Assessments of Children and Young People who are the subjects of Child Protection Plans (on the Child Protection Register) 1 April 2008 to 31 March 2009, Retrieved from http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/datastats1/guidelines/children/docs/CPR3GuidanceNotes0809.doc. on 26th July 2009, p.9.

Thursday, 9 July 2009

Mass lobby about the Badman Review

Dear Friends,

Re: Mass lobby about the Badman Review and White Paper: Your Child; Your Schools; Our Future: Building A 21st Century School System.

In response to a suggestion by an MP, some home educators are organising a mass lobby of Parliament on Tuesday 13 October 2009. Please keep that date free if you want to join in. The more people who come, the greater the impact will be.

I would also be grateful if you could email me atmasslobby@live.co.uk to let me know if you are coming. It would be good to have an idea of numbers and to be able to contact you with further details if necessary.

Please cross post this everywhere.

Claire Blades

===================================================

Below is an article prepared by Amicus Union for its members when they organised a mass lobby about equal pay.

HOW TO LOBBY YOUR MP

What is 'lobbying'?

Lobbying is using your right to meet your MP as one of his or herconstituents. You can do this either in your constituency or by visiting Parliament.

An MP should regard you as a constituent whether you voted for them or not. MPs are meant to "represent" each constituent'sinterests. This does not mean that they have to agree with you - after all each MP has up to 90,000 constituents - but it does mean they should listen and be prepared to pass on your views to the Government.

You should therefore use a meeting with your MP to try to:

* Give them the information they need about [the Badman Review]

* Influence their views

* Persuade them that many other constituents share your concerns

* Ask them to pass on your concerns to the Government, and

* Ask them to take appropriate action (and we suggest some below) to show that they support you.

Meeting your MP

In theory, you can turn up at Westminster any time that the House of Commons is sitting and request a meeting with your MP. But there is no guarantee that they will be there or have time to meet you, and in these days of heightened security, there is a strict limit on numbers within Parliament. When you are joining a mass lobby such as this, you should do everything you

can to arrange to meet your MP in advance.

ARRANGEMENTS IN ADVANCE

Contacting your MP

The best way to contact your MP is to write to him or her at the House of Commons, Westminster, London, SW1A 0AA. Most MPsalso use email, and should treat emails in the same manner as a letter. You can find out your MP's email address at the following website:

http://www.parliament.uk/

Arranging to meet your MP

There is a limit of 100 lobbyists at any one time in the Central Lobby - the area in the House of Commons where visitorstraditionally wait for MPs.

If you need to go to Central Lobby, you will enter through what is known as the St. Stephens entrance to the Commons. Stewards will be available to help you. Before you queue for the security check, inform a police officer that you have a meeting arranged with your MP and show them any correspondence your MP has sent to you. This should allow you to go straight into the

security checking area without queuing with the general public for tours of Parliament. Your MP or their staff will usually come to meet you in Central Lobby. You need to go to the desk in Central Lobby and ask the attendants to telephone your MP's office.

Tight security

Remember you will have to go through 'airport type' security to gain access to Parliament - on a busy day this can take at least 15 minutes - and you may need to queue until there is space.

What if you don't have an arranged meeting?

If your MP has agreed to meet you, but not given you any details of where and when, or if you have not already arranged a meeting with your MP, you will need to queue outside St Stephen's entrance.

The police will only allow 100 people, including lobbyists and other visitors, into Central Lobby at any one time. Pass through the security check and proceed to Central Lobby. Once there, go to the desk and ask for "a green card". This is a request for your MP to come and meet you and should be filled in and returned as directed. It is important that you make clear statement your reason for visiting on the card.

This is very important because, if you do not manage to meet with your MP, the card will then be sent on to him or her. Your MP should then respond directly to you and the more he or she knows about why you were at Westminster, the better.

The desk staff will take the card and officials will be asked to look for your MP and let him or her know that you are asking to meet with them. You should wait around for a while, but don't forget that lobbyists with firm appointments to meet their MP will also be waiting, so you should be prepared to give up waiting after 30 minutes or so.

Disabled access

If you are disabled, please telephone the Serjeant-at-Arms' office at the House of Commons, who will advise you of procedures for entering the building. (Phone 0207 219 3000 and ask the switchboard to put you through to the Serjeant's office). TheSerjeant's office do allow some parking where it is required by disabled people, but individuals will need to verify this with the office. It is usual for one of your MPs' staff to accompany you once you enter the building. You will need to arrange this with your MP in advance. Please notify the union if you have any special ambulatory needs or require any assistance.

Meeting with your MP

It is best to be as brief, clear and courteous as possible. If they send their researcher instead, treat them in the same way.

You should thank him or her for taking the time to see you, establish how much time they have, make two or three key points and - most importantly - ask them to follow up the meeting. (You can use any Briefings that may have been supplied to you but do point out how the issues directly affect you, your family and your workmates if possible).

Ask your MP to

*Raise your concerns with any relevant Ministers by meeting them and by writing to them.

*Continue to try and meet MPs in their constituency to follow up on what action they have taken or to raise the concerns with MPsyou are unable to meet with on the day.

Remember - do not be surprised if your MP only has a small amount of time to spare you. MPs will be very busy on the day, so don't take it personally. But make the most of the time you have with them.

Enjoy the lobby!

Remember - your action can make the difference!

Letter from Kenneth Fox, Clerk to the the Select Committee, DCSF

Children, Schools and Families Committee

House of Commons 7 Millbank London SW1 P 3JA

Tel 020 7219 6181 Fax 020 7219 0848 Email csfcom@parliament.uk Website www.parliament.uk/csf/

Prof. Bruce Stafford

7 July 2009

Dear Professor Stafford (hand written)

Thank you very much for your letter of 2 July, copying to the Committee your letter of 1 July to the Parliamentary Ombudsman, on the review of Elective Home Education. The Committee has received quite a lot of correspondence from others on the same issue, and it is very much aware of the criticisms which you and others make about the conduct of the Review. The Committee will shortly be taking decisions on subjects for future inquiry and I shall ensure that your letter is borne in mind when that discussion is held.

Yours Sincerely

Kenneth Fox (Hand written)

Kenneth Fox

Clerk of the Committee

Wednesday, 8 July 2009

A Letter going to all Local Authorities in England

Dear

Re: Proposed new duties in regard to Elective Home Education

As you will be aware, The Report on the Review of Elective Home Education by Graham Badman was released on

If implemented, Mr Badman's recommendations would place a significantly higher level of responsibility on Local Authorities for the registration, monitoring and assessment of all children educated otherwise than at school. In brief there are two basic changes that these recommendations would bring:

* compulsory annual registration for all home educating families, and

* compulsory visits to the homes of all home educating families by Local Authority officers who would have the right to interview children without their parents present.

We are writing to draw your attention to some implications of these proposed new duties.

1. Legal

Current legislation states that it is every parent's responsibility to ensure their child receives a suitable education. If this legal responsibility were to shift onto the Local Authority, it would lay the Local Authority open to legal action for failing to ensure that any child (whether in school or not) received a suitable education. Mr Badman's recommendations, should they become law, would be a significant step in this direction.

2. Staffing and systems

At present it is unclear how Mr Balls imagines your new duties would be carried out in practice. There are an estimated 50,000 - 80,000 home educated children to monitor, though this may be an under-estimate. The registration process in itself would more or less double the current workload of Local Authority staff who deal with home education.

A particular concern would be the sourcing of more personnel trained in the highly sensitive and specialist area of interviewing children about their safety as well as their educational progress. As you are probably aware, social work vacancies already stand at 14% nationally. If the recommendation from the Badman report is introduced Local Authorities could be required to speak with every child who is home educated and ascertain both their educational progress and

their safety. It is likely that Local Authority protocol would need to be established for best practice, thus each visit to each child could require two workers. As these visits must take place at least yearly and given the estimated number of home educated children, the pressure on Local Authority workers and Local Authority budgets could be immense.

While Mr Balls has not set a specific date for any changes to be introduced, the consultation regarding these recommendations ends on October 19th. Despite the enormity of the changes that are proposed, he has only allowed the minimum time for the consultation process and it may be the case that he wishes to rush these changes through as soon as possible.

A further worry is that the government appears to believe that the proposals would not increase the workload of Local Authority personnel. They have not carried out an impact assessment to accompany the consultation. Baroness Morgan of Drefelin who is a Labour Peer and the Parliamentary Under-Secretary with the DCSF has explained the reason for the lack of impact assessment, stating;

"We do not expect them [the proposals] to place any significant additional burdens on local authorities as most already monitor home education."

(http://www.theyworkforyou.com/wrans/?id=2009-06-29a.6.4&s=Home+education#g6.).

Mr. Badman's report confirms that only 20,000 home educating families are known to Local Authorities .There is an estimated further 30,000-60,000 home educating families in existence, so it is difficult to see how proposals to register and monitor all these families on at least a yearly basis would not place significant additional burdens on local authorities.

3. Financial

It is highly likely that such changes would require a rigorous and ongoing training programme for all members of staff involved with children. At present, Mr Balls has not committed any funding for the implementation of these ditional duties nor for the training that would be required for workers. We would encourage you to seek clarification on this matter at an early stage.

4. Ethical

Ethically, the rights to privacy and free association can be overridden when there is good cause. However, as Mr. Badman himself reported (paragraph 8.14 of the Review report):

"I can find no evidence that elective home education is a particular factor in the removal of children to forced marriage, servitude or trafficking or for inappropriate abusive activities."

Mr. Badman also states that (para 8.12 of the Review report):

"the number of children known to children's social care in some local authorities is disproportionately high relative to the size of their home educating population."

However he does not give details of how many Local Authorities this applies to, only stating that it is 'some'. He also does not detail how many of these 'known' children are known due to their special educational needs. He does not state which, if any, of these children are known to the Local Authorities because they are at risk of harm.

It is therefore unclear on what basis he is suggesting that compulsory visits to all home educating families would be a proportionate response to the supposed risk.

A recent nationwide poll of home educated children and young people found that 77% did not wish to speak to Local Authority officers about their education. There is a further danger, therefore, that the new duties imposed following the Badman review will directly conflict with your duty under section 53 of the Children Act 2004, to, where reasonably practicable, take into account the child's wishes and feelings with regard to the provision of services.

Consideration should also be given to the moral or ethical justification for potentially allowing children genuinely in need to go unprotected or unnoticed, due to the increased workload imposed on local authorities by the duty to annually monitor and interview reportedly 50,000 - 80,000 home educated children in the UK. Home educators are perplexed and worried by this very real possibility.

5. Relations with the community

Some Local Authorities have worked hard in recent years to build good relationships with their local community of home-educating families. There is a danger that the implementation of these recommendations would undermine that work.

Analysis of data provided by 70% of local authorities indicates that the proportion of children known to be electively home educated and actually considered to be at risk is less than half the proportion considered at risk in the general population. (http://tiny.cc/gdk8u)"

Many home-educating parents feel strongly protective of their children's autonomy. This is a common motivation for turning to child-led learning in the first place. There is a wealth of information on the positive aspects of autonomous or personalised learning and much evidence to suggest this community of learners and their families are functioning as a positive part of the general population.

In Graham Badman's Report on Home Education he wrote:

"I have sought to strike a balance between the rights of parents and the rights of the child, and offer, through registration and other recommendations, some assurance on the greater safety of a number of children." (para 11.2)

A survey carried out by Ann Newstead following the release of the Report sought to give home educated children (aged between 5 and 25 years) the opportunity to respond to this. An overwhelming 90% of the children who responded were against the idea of being interviewed without their parent or educator present.

(http://www.ukhome-educators.co.uk/Survey/childsurvey0609.htm).

Given the widespread anger aroused by this report within the home education community, and the commitment of home educating parents to respecting their

children's wishes about their education and privacy, we expect that implementing

the recommendations will not be straightforward for Local Authority officers on

the ground.

We believe that all these issues are worthy of consideration, and are relevant to any response which your Local Authority may make to the current consultation.

We enclose a collection of relevant Web links for your information.

DCSF Consultation on Home education - registration and monitoring:

http://www.dcsf.gov.uk/consultations/index.cfm?action=conSection&consultationId=\

1643&dId=990&sId=6089&numbering=1&itemNumber=2&CFID=22725695&CFTOKEN=43876675

Review report:

http://publications.everychildmatters.gov.uk/eOrderingDownload/HC-610_Home-ed.PD\

F

Response to the review from Ed Balls:

http://www.freedomforchildrentogrow.org/Ed%20Balls%20to%20Graham%20Badman%201106\09.pdf

2002 Research by Paula Rothermel of Durham University, on outcomes for home

educated children: http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00002197.htm

Results of poll of home educated children's wishes:

http://daretoknowblog.blogspot.com/2009/03/results-of-poll.html

If you are not already in a dialogue with home educators in your local area, and you would like to discuss these issues with directly affected families in person, please contact us at the email address below and we will endeavour to put you in touch with local parents who can give you any further information you need.

Yours sincerely

Mrs B Bodycote

on behalf of the Badman Review Action Group, an alliance of over 600 concerned

individuals.

badmanreviewactiongroup@yahoogroups.com

Imagine this

Imagine this. Your child is being bullied at school; it has had a devastating impact on his or her ability to learn and on their psychological and emotional health. You are very unhappy with the way in which the school has handled or failed to handle this. The situation is worsening. You seek to withdraw your child from school and make alternative arrangements for his or her education. But there is a new law that states you must apply for permission to de-register; you apply as instructed. You are refused.

How would you feel? What would you do?

Currently, British law recognises parents as their child's primary educators whether or not the child is currently at school;

the adults who best love and understand their child are those in law who have ultimate responsibility for their education and welfare and it is your judgement as a parent which counts; you decide what kind of education best suits your child; if it isn't working , you have the right and power to seek an alternative. A new government review seeks to overturn this time-honoured principle of British law and to replace the judgement and authority of the parents with that of the State.If it is passed, it will radically change the relationship of all parents to the State and seriously undermine the integrity of families.It will also replace the judgement of those who best love and understand the child with that of faceless bureaucrats whose focus is on delivering a standard policy and imposing a government agenda rather than on the well being of the child.

You can read about the review here; and remember, regardlesss of its title , the proposals would affect all parents.

http://www.freedomf

and petition for it';s agenda to be dropped here;

http://petitions.

warmest wishes,

Karen

Tuesday, 7 July 2009

Family Education Trust Response to the Review of Elective Home Education

Submission to the Home Education Review

Consultation Questions

1. Do you think the current system for safeguarding children who are educated at home is adequate? Please let us know why you think that.

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

Yes.

All children are protected within the same legal framework irrespective of educational setting. We are concerned that the headline given to the press release relating to the home education review, ‘Action to ensure children’s education and welfare’ suggests that specific action is required in relation to home educated children that is not required for children in school. Such an outlook betrays an unwarranted lack of trust in parents to fulfil their legal duties in relation both to the care and education of their children.

Children educated at home will generally receive a greater degree of monitoring and supervision from their parents than children at school receive from their teachers. The question appears to presuppose that home education raises special safeguarding issues. However, there is no more need for a specific safeguarding system for children educated at home than there is need for a specific safeguarding system for children who take private lessons in a foreign language, music or ballet.

Many children have been withdrawn from school to be home educated because of concerns about their personal safety. Parents of children in schools note with alarm the need for a police presence in a growing number of schools and welcome initiatives to effectively tackle bullying, violence and other anti-social behaviour, but children educated at home are not subject to such risks and dangers.

It is important to uphold the legal tradition whereby citizens of a free country are presumed innocent until found guilty. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, it may therefore be assumed that parents are fulfilling their legal responsibilities with regard to the care and education of their children. If such a presumption were more widespread, it would help to resolve many of the conflicts that have arisen between local authorities and home educating parents.

On the other hand, where there is evidence that parents are failing to provide a ‘full-time efficient education, suitable to [their] age, ability and aptitude and to any special needs [they] may have’, the authorities are empowered investigate and take appropriate action where necessary (Education Act 1996, s437). Also, under Section 47 of the Children Act 1989, local authorities are empowered to make enquiries and take action where necessary in cases where they have reasonable cause to suspect that a child in their area is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm.

The principle of not requiring any intervention on the part of the authorities unless ‘it appears’ to a local authority that parents are failing to fulfil their responsibilities is not a legal loophole as some have characterised it, but a provision that conforms to three key principles at the heart of UK and European law:

· parental responsibility (Section 7, Education Act 1996),

· respect for parental wishes and parental religious and philosophical convictions (Section 9, Education Act 1996, and Article 2, Protocol 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights), and

· the right to a private family life (Article 8, European Convention on Human Rights).

In keeping with these principles, the Elective Home Education Guidelines for Local Authorities state that ‘parents are not legally required to give the local authority access to their home’ and ‘where a parent elects not to allow access to their home or their child, this does not of itself constitute a ground for concern about the education provision being made’. The guidelines go on to say where informal enquiries are made, parents should be free to provide evidence in a variety of ways (para 3.6).

We are conscious that some education professionals and local authorities have been calling for the introduction of compulsory monitoring arrangements including a legal right of access to home educated children and possibly to the family home. However, we are not aware of any evidence demonstrating that compulsory monitoring and the legal right of access has any proven benefit for home educated children. In particular, for home educated children who associate education professionals with traumatic experiences in the past, compulsory monitoring with a legal right of access to the child would be a frightening prospect.

It should also be borne in mind that home educating families typically do not draw a distinction between education and family life – the two are very much intertwined. It is for this reason that many are so uncomfortable about compulsory registration and monitoring. They would feel that their family life were being monitored and their children surveilled to a degree not experienced by children attending school.

2. Do you think that home educated children are able to achieve the following five Every Child Matters outcomes? Please let us know why you think that.

a) Be healthy

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

Yes.

Before addressing each outcome separately, we would wish to make the observation that we are not aware of anyone – no matter how sceptical about home education – suggesting that home educated children are ‘not able’ to be healthy and safe etc. It was for this reason that we sought clarification regarding the purpose of this question before making our response. Unfortunately, officials were unable to assist, leaving us wondering whether it is genuinely considered an open question as to whether parents are competent to meet the basic needs of their own children.

We put it to officials in the DCSF that it is an insult to home educating parents to enquire whether they are able to keep their children safe and see to their health needs etc, and then, to add further insult, to ask, ‘Why do you think that?’ Have we really reached the point where parents have to provide evidence that they are able to care for their own children?

Our understanding of the Every Child Matters outcomes is that they are intended to help local authorities establish priorities in terms of policy development, and not to be used as targets for individual children. We are concerned that to apply the outcomes to individual home educated children in a way they are not applied to children in school is to misuse them.

The five outcomes cover very broad areas and are capable of subjective interpretation, making them unsuitable as measurements of the achievement of individual children. For example, we note that the word ‘well-being’ is used twice in Section 10 of the Children Act 2004 – ‘emotional well-being’ and ‘social and economic well-being’.

According to the DCSF research report, ‘What do we mean by “wellbeing”? And why might it matter?’ (October 2008), while the term features strongly in policy and delivery documents, there is no agreement as to its meaning. The report concluded that there was, ‘significant ambiguity around the definition, usage and function of the word “wellbeing”, not only within DCSF but in the public policy realm, and in the wider world’. It added that ‘the meaning and function of a term like “wellbeing” not only changes through time, but is open to both overt and subtle dispute and contest’ and recommended that the DCSF adopt a ‘low key but deliberate strategy to manage [its] position within this ambiguity and instability’. We would therefore suggest that it would be a hazardous exercise for local authorities to make judgments about the ‘emotional’ or ‘social and economic well-being’ of children in their area.

Turning now to Question 2(a), while parents are not able to guarantee the health of their children there is no reason to suspect that parents of home educated children will not show at least the same degree of vigilance for their health as those who send them to school.

In fact, home educated children may be spared many of the germs and bugs that circulate in the classroom, and since they spend more time with their parents, it is likely that any health concerns will be more swiftly identified and addressed.

We note that the document, ‘Every Child Matters: Change for Children’ defines ‘be healthy’ in terms of sexual health, healthy lifestyles and choosing not to take illegal drugs. In relation to these factors, there is no doubt that home educated children are more likely to be healthy than children in school because they are not subject to the same level of peer pressure and benefit from closer adult supervision.

b) Stay safe

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

Yes.

Like health, safety cannot be guaranteed in any setting. Accidents do happen, whether at home, school, on the roads, or in sporting activities etc. However, parents who home educate their children are no less able to look out for their safety than the parents of children who are in school for 30 hours per week, 39 weeks per year and are arguably better placed to ensure their safety than are parents who send their children to school.

The ‘Every Child Matters: Change for Children’ document includes safety from ‘bullying and discrimination’, from ‘violence and sexual exploitation’, and from ‘crime and anti-social behaviour’ in its definition of ‘stay safe’. In relation to these factors, under the care and protection of their parents, home educated children will be far safer than children educated at school.

c) Enjoy and achieve

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

Yes.

Like health and safety, enjoyment and achievement cannot be guaranteed in any sphere. Illness, sickness, sadness and failure are part and parcel of life and affect everyone, children included. However, no caring parent wishes to inflict the harsh realities of life on children, and where disappointments and tragedies occur they will want to support them in every way possible.

Taken at face value, the question appears to be whether home education is compatible with enjoyment and achievement, and the answer to that is an emphatic ‘yes’. Does the review team really imagine that parents are home educating their children in order to deprive them of any enjoyment in life and to ensure that they fail in whatever they apply themselves to?

Research undertaken by the National Home Education Research Institute (NHERI) shows that home educated children in the United States typically score above average on measures of social, emotional, and psychological development (see http://www.nheri.org/ ). Children and young people educated at home participate in social and educational activities both with other home educating families, and with the wider community.

In terms of their academic achievement, research from the United States demonstrates that home educated children typically score 15 to 30 percentile points above public-school students on standardised academic achievement tests, regardless of their parents’ level of formal education or their family’s household income.

The question appears to imply that while the enjoyment and achievement of children in school is guaranteed, there is some doubt as to whether home educated children ‘are able to achieve’. In view of the fact that the Confederation of British Industry reports that 41 per cent of employers are concerned at employees’ lack of basic literacy skills and 39 per cent at their level of numeracy skills (‘Taking stock: CBI education and skills survey 2008’, at http://www.cbi.org.uk/pdf/skills_report0408.pdf ), we would suggest that confidence in the ability of vast numbers of children educated at school to achieve even in the areas of basic literacy and numeracy is misplaced.

The ‘Every Child Matters: Change for Children’ document defines enjoyment and achievement almost entirely in relation to attendance and achievement at school, but thousands of children in the UK and elsewhere are demonstrating that school does not have a monopoly on achievement or enjoyment. In fact, if children in school were achieving this outcome, there would not be anywhere near the level of truancy and exclusions, and neither would a police presence be necessary.

d) Make a positive contribution

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

Yes.

Home educated children typically make a very positive contribution to their families, to their own social network and to the wider community in an age-appropriate way. Without the constraints of homework, home educated young people are able to devote more time to voluntary work in church and other community groups.

Many home educating parents place a strong emphasis on providing opportunities for their children to serve the needs of others, and home educating families are often noted for the practical care they are able to give to the sick, the elderly and the housebound.

e) achieve economic well-being

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

Yes.

In responding to this question, we are assuming that we are being asked whether children who have been home educated are employable upon completion of their full-time education.

Some home educated children enter employment straight from home, while others pursue additional studies at Further Education colleges or universities prior to embarking upon their careers. We are not aware of any evidence of children being placed at a disadvantage as a result of home education. In many cases, the fact that young people who have been home educated tend to be less peer-dependent and better able to relate across a broader age spectrum than those who have been in school, is a specific advantage when they enter the workplace.

Home educated young people often develop personal study skills at an earlier age than those who attend school. This, too, can stand them in good stead if they are required to work without close supervision in the course of their employment.

3. Do you think that Government and local authorities have an obligation to ensure that all children in this country are able to achieve the five outcomes? If you answered yes, how do you think Government should ensure this?. If you answered no, why do you think that?

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

No.

We queried the scope of this question with the review team and DCSF officials on 21 January as it was unclear what kind of obligation was being referred to. However, four weeks later, they have declined to offer any clarification, advising us that we should interpret the question in our own way. We would have preferred a definitive explanation as that reduces the risk of our attempting to answer a question that has not been asked, which is not helpful to anyone.

In the absence of an explanation, we have assumed that the question is asking whether the government and local authorities have a legal obligation to ensure that all children in this country are able to achieve the five Every Child Matters outcomes.

Section 175(1) of the Education Act 2002 places local authorities under a duty to ‘safeguard and promote’ the welfare of children, and Section 10 of the Children Act 2004 requires local authorities to promote co-operation with partners and other appropriate agencies with a view to improving the well-being of children in their area in relation to:

(a) physical and mental health and emotional well-being;

(b) protection from harm and neglect;

(c) education, training and recreation;

(d) the contribution made by them to society;

(e) social and economic well-being.

There is a clear difference between ‘safeguarding and promoting’ children’s welfare and aiming to improve their well-being on one hand, and ‘ensuring that all children are able to achieve the five outcomes’ on the other. It is simply not within the power of central or local government to ‘ensure’ that all children are healthy, safe, enjoy and achieve, make a positive contribution and achieve economic well-being.

If the government or local authorities were to be placed under a legal obligation to ‘ensure’ that all children achieve the five Every Child Matters outcomes, they would be opening themselves up to litigation from parents and children who considered that they had failed to achieve one or more of the outcomes.

4. Do you think there should be any changes made to the current system for supporting home educating families? If you answered yes, what should they be? If you answered no, why do you think that?

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

No.

There is no ‘current system for supporting home educating families’. As the Elective Home Education guidelines make clear:

‘Local authorities do not receive funding to support home educating families, and the level and type of support will therefore vary between one local authority and another.’

As a minimum, local authorities are advised to provide clear and accurate written information on elective home education that sets out the legal position, but any additional support is discretionary (Elective Home Education: Guidance for Local Authorities, DCSF 2007, para 5.2).

We are concerned that, notwithstanding the guidelines issued in 2007, some local authorities are still failing to provide accurate information on the law relating to elective home education. There have been instances where parents have been incorrectly advised that they are legally required to register with the local authority and to receive periodic home visits, for example. Another concern that has been expressed is that home educated children and their parents are frequently treated in a less than courteous way by truancy patrols, who are often not familiar with the fact that home education is a legal option and that home educators are not obliged to observe school hours, days or terms (Elective Home Education guidelines, para 3.13).

While we would welcome action to ensure that local authority officers and truancy patrols are better informed of the law and guidance relating to home education, we would not be in favour of establishing a mandatory support system for home educators. Home educators receive advice and support from a range of sources and do not always feel that the local authority is suitably equipped or best placed to provide the support they need.

A better approach might be for local authorities to advertise what services they are willing to offer to home educators and then to leave it up to individual families to decide whether or not they wish to avail themselves of what is on offer. In this way, support can be provided to those who welcome it, without the local authority imposing ‘support’ on families who do not require it.

5. Do you think there should be any changes made to the current system for monitoring home educating families? If you answered yes, what should they be? If you answered no, why do you think that?

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

No.

There is no ‘current system for monitoring home educating families’. The Elective Home Education guidelines state:

‘Local authorities have no statutory duties in relation to monitoring the quality of home education on a routine basis. However, under Section 437(1) of the Education Act 1996, local authorities shall intervene if it appears that parents are not providing a suitable education’ (para 2.7, emphasis in original).

In a reference to the duty of local authorities to safeguard and promote the welfare of children under Section 175(1) of the Education Act 2002, the guidelines state:

‘Section 175(1) does not extend local authorities’ functions. It does not, for example, give local authorities powers to enter the homes of, or otherwise see, children for the purposes of monitoring the provision of elective home education’ (para 2.12).

However, where there are grounds for concern about the welfare of a home educated child, the local authority is empowered to act:

‘[L]ocal authorities have general duties to make arrangements to safeguard and promote the welfare of children (section 175 Education Act 2002 in relation to their functions as a local authority and for other functions in sections 10 and 11 of the Children Act 2004). These powers allow local authorities to insist on seeing children in order to enquire about their welfare where there are grounds for concern (sections 17 and 47 of the Children Act 1989). However, such powers do not bestow on local authorities the ability to see and question children subject to elective home education in order to establish whether they are receiving a suitable education’ (para 2.15).

In our view, the current guidelines are clear and serve as an adequate safeguard, providing protection for children without interfering with the right of home educating families to respect for their private and family life. There is no need to introduce a system of routine monitoring.

Most home educators view home education as part of their family life. We do not see any compelling reason why children who continue to experience family life during normal ‘school hours’ should be deemed in need of additional safeguarding or monitoring any more than families where children are out of the house between 9.00am and 3.00pm during term-time. There would be an uproar if the government were to propose routine welfare checks on all children during school holidays and at weekends. Such an intrusion would rightly be regarded as a breach of family privacy, and home educating families regard routine monitoring in the same way.

Local authorities do not conduct routine safeguarding checks on pre-school aged children who are cared for by a parent at home and we see no reason why that should change once a child reaches the age of five.

We are conscious that some local authorities are calling for a statutory definition of ‘suitable education’. However, we would suggest that the existing law is sufficient in that it clearly states that education must be suitable to the child’s ‘age, ability and aptitude and to any special needs he may have’. In addition, case law has established that a ‘suitable’ education is one which ‘primarily equips a child for life within the community of which he is a member, rather than the way of life in the country as a whole, as long as it does not foreclose the child’s options in later years to adopt some other form of life if he wishes to do so’ (R v Secretary of State for Education and Science, ex parte Talmud Torah Machzikei Hadass School Trust). We are not sure that it is possible to go beyond this without trespassing on the rights of parents to educate children according to their wishes and in accordance with their religious and philosophical convictions.

Some local authority officers have suggested that home educating parents need to be monitored more frequently than schools are inspected because of other checks and balances in place within the school system. However, this demonstrates a lack of respect for parents and a suspicious mindset.

The law is clear that parents are responsible for the education of their children. If they choose to send them to school, they still bear the legal responsibility for ensuring an efficient education. Schools are therefore operating as servants of the parents and are accountable to parents. It is for this reason that schools need to be inspected, to provide parents with a basis on which to decide between different options for the education of their children and to satisfy themselves that the school is delivering an efficient education. However, where parents elect to personally oversee the education of their children, either by undertaking most or all of it themselves or by employing tutors, there is no need for such close inspection or monitoring, unless ‘it appears to the local authority that a child of compulsory school age in their area is not receiving suitable education’, in which case local authorities are empowered to take appropriate action.

The current legal framework for home education is consistent with British legal traditions and with international human rights instruments, and pays due regard to parental responsibilities and family privacy. We would be wary of introducing legislation that would in any way undermine parents and suggest a lack of trust.

We are not sure that the strengths and benefits of the present framework are always appreciated:

· it permits flexibility – where support is needed and requested it can be given;

· where parents are fulfilling their responsibilities and do not require support or intervention, the local authority has no obligation towards them;

· scarce resources are therefore not wasted on monitoring families who neither need nor want local authority involvement;

· Local authority resources are freed up to address situations where ‘it appears to them’ that a child is not receiving suitable education.

If local authorities were to be given the statutory duty to monitor the education provision of every child in its area not registered at a school, they would be liable to legal action if they were deemed to have failed in their duties. Two possible scenarios come to mind:

(a) If a home educated child has been subject to regular compulsory monitoring by the local authority but, at the end of his/her years of compulsory education, considers that the local authority has failed to ensure that his/her parents have provided him/her with a suitable education, he/she could sue the local authority for negligence.

(b) A home educated child who suffered (whether physically, emotionally or academically) as a direct consequence of being forced by a school attendance order to return to school could bring a case against the local authority.

While it is true that scenario (b) could theoretically occur under the present legal framework, an extension of the powers and duties of the local authority would make both scenarios more likely.

6. Some people have expressed concern that home education could be used as a cover for child abuse, forced marriage, domestic servitude or other forms of child neglect. What do you think Government should do to ensure this does not happen?

· Yes

· No

· Not Sure

· No Response

It is very difficult to respond to unsubstantiated allegations. It would therefore have been helpful had the consultation paper stated which ‘people’ had expressed such concerns and on the basis of what evidence.

We are not aware of any evidence associating home education with child abuse, forced marriage, domestic servitude or child neglect, and certainly registration at a school offers no assurance that such things will not happen. Ultimately, the government can never ‘ensure’ that children are not abused or neglected, irrespective of education setting.

Home education is no more a ‘cover’ for abuse than is sending a child to school, to scouts, to music classes, or engaging in social work, fundraising for a children’s charity, or taking an active role in local politics. The question appears to betray a suspicious mindset. We see no need to treat parents with suspicion simply on the basis that they are exercising their right under Section 7 of the Education Act 1996 to educate their children otherwise than at school.

There is no basis on which to treat home education as a risk factor in child abuse. It is, however, well-established that child abuse is disproportionately found in families where children are not brought up by their two natural parents, and particularly where the child’s natural mother is cohabiting with a partner who is not related to the child (Robert Whelan, ‘Broken Homes and Battered Children’, Oxford: Family Education Trust 1994). Nevertheless, it would be regarded as unacceptable and highly discriminatory to routinely monitor or introduce safeguarding measures for all children not living with their two natural parents. If it is unacceptable to introduce special safeguarding measures where there is an established link between child abuse and family structure, it should be ever more unacceptable to contemplate routinely monitoring home educating families where there is no established link.

Where a local authority has ‘reasonable cause to suspect that a child who lives, or is found, in their area is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm’, it is empowered to ‘make, or cause to be made, such enquiries as they consider necessary to enable them to decide whether they should take any action to safeguard or promote the child’s welfare’ (Children Act 1989, s47).

Recent high profile cases of child abuse have highlighted a failure on the part of the authorities to employ the powers that they already have. There is no evidence that additional powers are required.

To impose a system of routine monitoring of home educating families would represent a breach of their right to a private and family life and constitute a waste of public resources. It should be borne in mind that schoolchildren spend far less time in school than away from school. Yet if we were to apply the same suspicious mindset to their parents that ‘some people’ are applying to home educating parents, we would soon cease to live in a free society.

ADDITIONAL OBSERVATIONS

The burden of consultation

We are concerned that this review of home education is being undertaken little more than a year after the Elective Home Education Guidelines for Local Authorities were finalised following a thorough and extensive period of consultation. We understand that the present review may give rise to a full 12-week public consultation later in the year. In this regard, we would refer to Criterion 5 of the Better Regulation Executive Code of Practice on Consultation in relation to ‘The burden of consultation’:

‘Keeping the burden of consultation to a minimum is essential if consultations are to be effective and if consultees’ buy-in to the process is to be obtained…While interested parties may welcome the opportunity to contribute their views or evidence, they will not welcome being asked the same questions time and time again.’

The consultation document

We are concerned that the consultation document is very brief and fails to set the review in any legal or historical context. No attempt is made to set out the current legal framework or to explain current safeguarding procedures, and there is no reference to the Elective Home Education guidelines. There is also no explanation of the Every Child Matters initiative and its status, and no explanation of the specific concerns that have given rise to the review.

As indicated in the responses given above, we are concerned that the questions are unclear and ill-defined, giving rise to a range of possible interpretations. We requested clarification on the meaning of questions 2 and 3 in particular at the very outset of the review on 21 January, but officials declined to offer a response beyond stating that respondents were free to ‘choose to interpret them in their own way’.

The questionnaire to local authorities

In his letter to Directors of Children’s Services and Lead Members for Children and Young People, Mr Badman appears to be labouring under the misapprehension that local authorities are responsible for ‘ensuring that all children are able to achieve the five Every Child Matters outcomes’. However, as we observe in our response above, while local authorities are responsible for ‘safeguarding and promoting’ the welfare of children, they have no duty to ‘ensure’ it and, even if they did, it would be completely outside their power to do so.

The local authority personnel who ‘feel that they are not able to ensure that all home educated children are able to [achieve the five ECM outcomes]’ are therefore demonstrating a failure to understand the law and the limitations of their role. This suggests that the entire review may rest on a false premise.

The letter, together with the questions that follow, also seems to imply that local authorities are required to have arrangements in place for supporting and monitoring home educating families. However, the Elective Home Education Guidelines for Local Authorities clearly state that: ‘local authorities have no statutory duties in relation to monitoring the quality of home education on a routine basis’ (para 2.7) and that: ‘Section 175(1) does not give local authorities powers to enter the homes of, or otherwise see, children for the purposes of monitoring the provision of elective home education’ (para 2.12).

At several points the questions asked of local authorities do not appear to take account of the guidelines. To take just one example, Question 46 defines full-time education for home educated children as ‘20 hrs a week’. The guidelines, however, specify:

‘Children normally attend school for between 22 and 25 hours a week for 38 weeks of the year, but this measurement of “contact time” is not relevant to elective home education where there is often almost continuous one-to-one contact and education may take place outside normal “school hours”.’

The guidelines go on to state that home educating parents are not required to have a timetable, observe set hours during which education will take place, or follow school hours, days or terms (para 3.13).

The terms of reference

The terms of reference for the review appear to assume that there are barriers to local authorities and other public agencies in carrying out their responsibilities for safeguarding home educated children. The assumption is also incorrectly made that local authorities have a responsibility to ‘ensure’ that the five Every Child Matters outcomes are being met. The words ‘ensure’ or ‘ensuring’ feature three times in the four bullet points. This failure to appreciate the fundamental difference between ‘promoting’ and ‘ensuring’ seems to run throughout the review.

Home educated children are referred to as though they are a particularly vulnerable and ‘at risk’ group, when in reality they are simply children whose parents are exercising their right under Section 7 of the Education Act to educate them ‘otherwise’ than at school.

The fact that the terms of reference refer to ‘the extent to which claims of home education could be used as a “cover” for child abuse’ indicates that an assumption has already been made that home education is being used as a ‘cover’. For reasons given above, we object to this characterisation.

Under the third bullet point, a reference is made to ‘supporting’ home educating families in order ‘to ensure’ that they are undertaking their duties. We are uncomfortable about the use of the words ‘support’ and ‘ensure’ in such close proximity as they appear to imply an element of compulsion about the ‘support’ being offered. We are concerned that the terms of reference show a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of the local authority as set out in the home education guidelines at this point.

The final bullet point refers to the ‘current regime for monitoring the standard of home education’. However, as stated in the Elective Home Education guidelines, ‘local authorities have no statutory duties in relation to monitoring the quality of home education on a routine basis’ (para 2.7).

20 February 2009

Family Education Trust

Jubilee House

19-21 High Street

Whitton

Twickenham

TW2 7LB

http://www.famyouth.org.uk/